If two months ago someone would have told me where we are today, I would have never believed them. Businesses are shuttered, surgeries canceled and postponed indefinitely, standard-of-care medical treatments being suspended or delayed, people attending important medical appointments and learning life-changing information without the support of a loved one. It is stunning how much has changed and how quickly we’ve all had to adapt to life in the time of Covid-19.

At Genetic Support Foundation we’ve met with patients through both telehealth and in-person visits for a few years now, and until a month ago I had a pretty even balance of time with patients whom I met via video and those I saw face-to-face in a clinic setting. In mid-March, as we all became more aware of the insidious manner in which this virus could spread through unsuspecting, asymptomatic carriers, we became concerned that many of our genetic counselors were traveling to see patients at multiple different sites. I was especially concerned given that many people at these clinics were in vulnerable populations and at greater risk for serious complications, including cancer patients and pregnant women.

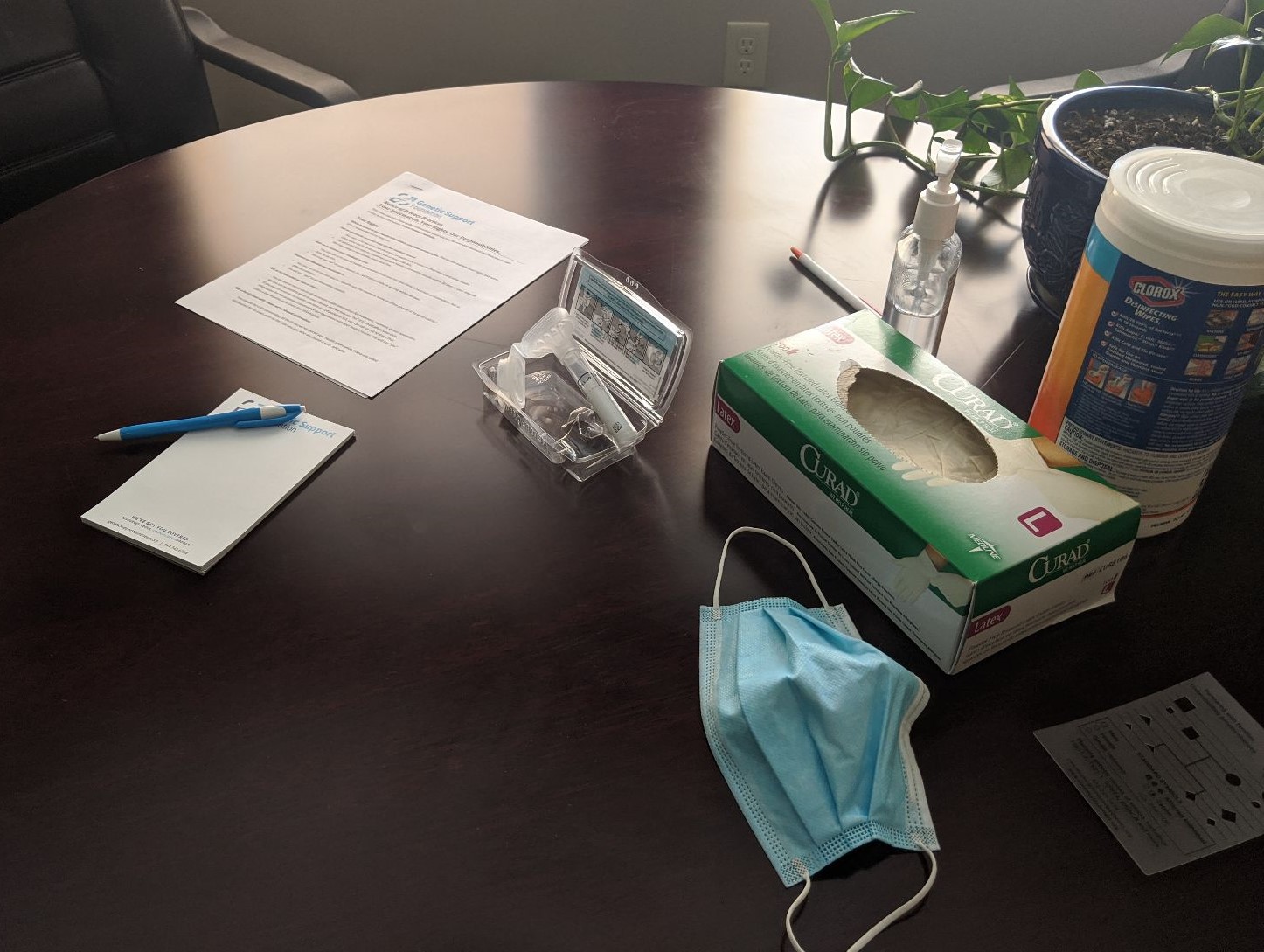

We quickly adjusted with our partner clinics to bring as much of our services to telehealth as possible to minimize contact and hopefully decrease risk for our patients. We have been flexible, and still see some patients in the clinic when needed to coordinate their care in a timely way. In these cases, we are taking all precautions to keep everyone safe–wearing masks, keeping a distance, lots of handwashing, and sanitizing of our spaces. I’m grateful we were able to make this transition so smoothly, building on our past experience, and for a brief moment it seemed that we would be able to maintain some normalcy in our day-to-day work by continuing to connect with patients. Some days, these circumstances wear us down and make those connections more difficult, but I know it will not always be this way. Finding normalcy in some moments now doesn’t mean that this will be a new normal.

Genetic Counseling as an Extension of Crisis Counseling

Just as the Covid-19 crisis began unfolding in my home state of Washington in February, I attended the Texas Society of Genetic Counselors annual education conference where I had the opportunity to hear Krista Redlinger-Grosse, PhD, genetic counselor and psychologist, give a talk on burnout and compassion fatigue in genetic counseling. During the talk Dr. Redlinger-Grosse compared genetic counseling to crisis counseling. I had never considered this, and this point resonated with me. As genetic counselors we often speak with patients who are in crisis. Perhaps they just learned they have cancer, or that their baby may have a serious medical concern, or maybe they have just learned that a life-altering disease runs in the family. Our days as genetic counselors can be a series of stressful conversations with people whose lives are being turned upside down. Dr. Redlinger-Grosse pointed out that the nature of our work and some of our frequent personality characteristics as genetic counselors (perfectionism, trait anxiety, low external locus of control) can increase the risk of burnout.

Despite my many years of working as a genetic counselor I can truly say that I don’t often identify a feeling of burn out. I love my work as a genetic counselor and find the time I spend with patients to be incredibly grounding, even when the encounters are intense and stressful. I have described to my colleagues that genetic counseling is like my meditation–even when faced with the most chaotic of personal circumstances, once I am face-to-face with a patient, all other thoughts and worries disappear for a time and I am able to focus only on that person I am working with and their situation. I think this is the case because I derive a lot of personal satisfaction from work in which I feel I can help others. I also feel that genetic counseling, like all caring professions, gives an opportunity to practice empathy–to see the world through the eyes of another.

Covid Has Changed How We Care

Genetic counseling in this time of Covid-19 is challenging me in new ways. Honestly, it is a struggle to see how genetic counseling fits into the larger picture of healthcare for our patients at this time of crisis. To give an example, people often use information from genetic counseling and genetic testing to guide their surgical decisions when diagnosed with cancer, including breast and colon cancer. A few weeks ago, a patient of mine received a call shortly after her appointment with me that her breast cancer surgery was canceled, as it was not deemed urgent/emergent and would be rescheduled at some time in the future. I’ve also had more conversations lately about whether genetic test results would change surgical plans at this time.

In the pre-pandemic world, many women diagnosed with breast cancer may elect to undergo a bilateral mastectomy rather than a lumpectomy if they carry a mutation in a gene such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 that puts them at high risk for a second breast cancer. These days we have another variable to factor into surgical decision-making. Given that a bigger surgery increases the risk for complications, and means more time recovering in the hospital, many are concerned that this could increase Covid-19 infection risk too. Not to mention, people are not allowed to have visitors in hospitals in most parts of the country, so a bigger surgery means more time apart from loved ones. Additionally those who learn now that they are at an increased risk for cancer due to an inherited mutation may have additional anxiety, as they will be stuck with this information in a holding pattern, unable to access cancer screenings or undergo risk-reducing surgeries.

Covid-19 is affecting prenatal genetic care as well. In some of the clinics where we support genetic counseling services, we are seeing an uptick in the number of diagnostic tests performed, such as amniocentesis. One of our genetic counselors speculated that perhaps people were drawn to these tests that could offer more certainty, at a time in life when everything else feels so very uncertain. On the flip side, we are seeing people who once planned on diagnostic testing now forgoing it due to concerns of transmitting a virus should they be infected and not yet know. And most prenatal clinics are also not allowing visitors – this means women are having their ultrasound, undergoing amniocentesis, and receiving life-alternating news about a prenatal diagnosis, all without their partner. As genetic counselors we are more and more frequently meeting with patients on the other end of a video screen where we cannot pass the tissue box or offer a hug.

Increasing Our Compassion for Ourselves and Others

Of course, there are some bright spots as well. It is wonderful to be able to share news of a negative result for a familial mutation. It can be such welcome news to patients who can now cross hereditary cancer risk off their list of worries – I have found these phone calls often bring tears of relief. To be able to patch in an expectant father to a video conference when he can’t join his partner at the clinic, and to be able to share information and encouragement, is a wonderful use of the technology and helps keep us all connected

It all feels more than we can bear sometimes. Our patients are definitely under more stress than usual as all of us are in crisis and are separated from so many of the things that we commonly rely on for support and comfort. The circumstances we as genetic counselors find ourselves in at this time also increase our personal stress. Our lack of control in how we help our patients may decrease satisfaction with our role and could lead to greater compassion fatigue.

A powerful quote by Jim Rohn I jotted down during the talk at the TSGC, “The greatest gift you can give somebody is your own personal development. I used to say, ‘If you will take care of me, I will take care of you. Now I say, I will take care of me for you, if you will take care of you for me.’”

This is advice we should all live by and could be especially helpful at this time. As best we can through this crisis, let us keep caring for ourselves so we can continue to care for others.

Dr. Redlinger-Grosse shared this self care wheel which may be a helpful exercise. She also shared this Professional Quality of Life Test which is a tool that ultimately provides scores in three areas: 1) Compassion Satisfaction, 2) Burnout and 3) Secondary Traumatic Stress as related to your work. This may be a useful assessment for any of us to take right now and maybe again over time to check the pulse of how we are doing emotionally at work and in our lives.