By Katie Stoll

The Polygenic Embryo ELSI Research “PEER Group”, an NHGRI-funded research consortium that aims to build an initial framework for the consideration of the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of Polygenic Embryo Screening (PES), recently hosted a conference titled, Ready or Not? The Science and Ethics of Polygenic Embryo Screening. I was glad to take part in this conference as one of a diverse group of stakeholder representing viewpoints on this controversial topic. The agenda is linked here and you will see perspectives from genetic counselors, reproductive endocrinologists, statisticians, bioethicists, legal scholars, professional society leaders, government regulators, and the PES industry were all included.

Polygenic scores, or polygenic indexes, are based on data from genome wide association studies (GWAS) and provide single value estimates of an individual’s probability of a trait, health concern, or phenotype. In a nutshell, GWAS studies are performed by comparing small variations in genetic information between groups of people who express a certain trait, condition, or characteristic and those who do not. Think of them as an estimate of how much your normal DNA variants are similar to those of a particular group (i.e., those with a condition versus those without it). They will always represent probabilities – not certainties, and the collection of genetic variability that may be present in one group more commonly than another does not mean that the variants themselves are in any biological way connected to the trait.

Polygenic screening of embryos involves biopsying the trophectoderm of an embryo and performing genetic studies on those cells. There are genetic testing companies that are offering PES to predict the risk of common conditions, such as diabetes, cancers, and psychiatric disorders.

We at Genetic Support Foundation have significant concerns about PES and we will be sharing more in the coming months. For this post, I would like to focus simply on the perspective that I presented at the PEER Group conference which considers how commercial incentives may drive adoption of PES moving forward and what that could mean for patients.

A bit of background about me that I don’t usually include in my bio but is relevant for this meeting is that in the years prior to going to school for genetic counseling I worked as a medical assistant at the reproductive endocrinology and infertility clinic at the University of Washington. I witnessed firsthand the vulnerability and desperation of individuals going through fertility treatments. I also saw the dedication of the physicians, nursing, and embryology lab staff doing their best to help these patients to hopefully become pregnant and bring home a baby. Through my role as a medical assistant in this clinic, I would be one of the first to meet patients when they started their care in the clinic, bringing them to the back office, taking vital signs, and entering some initial questions in their chart. Through my role as a medical assistant in this clinic, I would be one of the first to meet patients when they started their care in the clinic. I was often the first person they’d share their questions and concerns with. I was there with them through every step of the process, from taking their vitals, to assisting with procedures such as egg retrievals and embryo transfers, to escorting them to the recovery room and keeping them company while they waited, often supporting them as they shared their hopes and worries, as well as providing a much needed distraction.

As I was recalling my time in the fertility clinic I remembered a funny thing about this post-embryo transfer time. I was instructed to elevate the foot of the patient’s bed so they would be lying at an angle (Trandelenburg position) for about 20-30 minutes after their procedure. The idea was that by elevating the patient’s pelvis it would give the embryo a chance to “settle in,” without the forces of gravity working against it. I remember asking one of the physicians I worked with at the time – is this for real? Does it really help improve the chance that the embryo will implant and that a pregnancy will occur? I was told that there were no studies to prove that it improved outcomes, but it made sense to them that it could help so why not?

25 years later and there is no evidence to show that patients placed in the Trendelenberg position have better IVF outcomes, and in fact, a recent meta analysis of studies evaluating the question of bedrest versus immediate ambulation after embryo transfer concluded that bedrest of any kind does not improve live birth rate. My informal survey of the Reproductive Endocrinologists at the PEER conference also indicated that this practice of having patients rest with feet in the air is no longer commonly done these days.

I share this history as an example of what I have come to see is a very common practice in fertility medicine – the tendency to try things that in-theory may help improve the odds of pregnancy, even before (and typically without) evidence that supports that these interventions are beneficial. Placing patients in the Trandelenberg position for 20 minutes following an embryo transfer seems like a relatively low risk and inexpensive intervention. However, this does not hold true for many other interventions and tests commonly used in the fertility space today, often referred to as “IVF add-ons”. It is my prediction that PES will be increasingly promoted as an IVF add-on, with claims of improving pregnancy outcomes whether or not there is evidence to support that this is the case.

I do not consider myself to be an expert in PES. However, I have seen many patients grapple with the uncertainty that comes from other interventions and tests that are commonly used in fertility care, and I would like today to draw on some of those experiences to provide insight on what we might expect to develop with PES. The primary drivers behind many of these tests that are utilized in reproductive healthcare are the commercial interests of those who seek to profit from the sales of these tests, a driving force that may not always prioritize the best interests of the individual patient.

Two tests I would like to begin discussions with are Expanded Carrier Screening (ECS) and Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy (PGT-A).

Most patients going through fertility care these days are offered carrier screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions. In fact, these expanded carrier screenings are considered a routine part of fertility care at some clinics, and may even be required by some clinics. Where carrier testing previously focused on a small number of genes and conditions, next generation sequencing has made it possible to screen for dozens, even hundreds of genes on one panel. There are a number of labs that offer ECS panels, and while there is no standard that all labs offer, it is not uncommon to see panels that include analysis of >500 genes. There is tremendous variability in what is included, and a challenge is that most of the genes on these panels are associated with quite rare genetic conditions, for which we have never screened the general population for and thus we don’t know the full spectrum of variation seen in these genes. For this reason, it is difficult to predict the clinical outcomes for many variants that are reported on carrier screening panels today. This leaves us often counseling patients about information we may only be guessing at, about the possibility for adult onset disorders, and about uncertain outcomes for their future offspring as related to ECS.

Another technology I’d like to highlight is preimplantation screening for aneuploidy, commonly referred to as PGT-A. PGT-A was introduced into clinical practice ~20 years ago with the idea being that the ability to select euploid embryos, those predicted to have the typical 46-chromosome complement, may see better outcomes from IVF. Aneuploidy, cases where there are extra or missing chromosomes, is known to be a common cause of miscarriage, as well as the cause for some conditions such as Down syndrome and trisomy 18, which occur more commonly with increasing parental age.

PGT-A was introduced into clinical practice based on this theory, and uptake of PGT-A has grown dramatically over the last decade despite much controversy and a growing body of evidence that indicates that overall IVF outcomes may not be improved by PGT-A for most patients. In 2019 the results from a multicenter trial, referred to as the STAR trial (Single Embryo TrAnsfeR of Euploid Embryo) were published and showed a similar live birth rate per intention to treat in those who underwent PGT-A and those who did not. In 2021 there was a large prospective trial published in the NEJM, which actually reported that the live birth rate was lower for patients who underwent PGT-A.

There is also great concern that there is much we don’t know about the early development of the embryo and that some embryos deemed as aneuploid, and so discarded or not transferred, may have had the potential to result in viable pregnancies. Still, the use of PGT-A seems to only be increasing, and despite a growing body of evidence regarding the lack of benefit, PGT-A laboratories and clinics market these tests as definitively improving the chance to have a healthy baby. Meanwhile, both the labs and the clinics have financial incentives to encourage utilization of PGT-A.

I’d like to share a couple of patient stories to illustrate how these technologies can play out in ways that don’t seem to be helping patients.

First, a couple referred for genetic counseling after having undergone expanded carrier screening in the fertility care setting. Their understanding was that this carrier screening would determine if they were carriers for any “serious conditions”. They were both found to be carriers for several conditions, including one match: both had variants in the GJB2 gene. Variants in GJB2 are associated with autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss, typically presenting with hearing loss at birth. Complicating matters for this couple is that while they carried different variants, both were described by the testing lab as having variable penetrance – meaning that some individuals who had these variants paired with another one (and so would be expected to show symptoms) may never develop hearing loss. There was very little in the medical literature to draw on about what to expect when these variants were paired together, and so we could only offer that a baby who inherited both of these variants could have hearing loss to a variable degree or may not at all. Prior to being referred for genetic counseling, the couple proceeded with IVF and did PGT-A as well as PGT-M (M=monogenic conditions, in this case testing for the GJB2 variants). The results left the couple feeling stuck – all of the embryos either had both of the GJB2 variants, were reported as aneuploid, or had “inconclusive” results. This couple agonized about what to do with these results, and whether the clinic would even allow them to proceed with pregnancy with one of their embryos.

In another example, a patient was referred for genetic counseling at 12 weeks of pregnancy. She was referred with the indication that she and her partner were both carriers for cystic fibrosis, however, it was noted in the referral that she had undergone preimplantation genetic testing and the embryo was known to be negative for the parental CFTR mutations. In review of the records, we saw that while the patient’s husband carried a common classic pathogenic variant in the CFTR gene, in fact the patient carried a polymorphism commonly known as the “5T allele” with an 11TG tract. The 5T allele is very common with ~10% of the population carrying it, and by itself it does not cause classic cystic fibrosis. There is a small possibility that the 5T allele when paired with a pathogenic variant may cause some mild CFTR-associated symptoms such as an increased risk for sinus problems or asthma, or contribute to infertility. But it does not cause what we commonly think of as classic cystic fibrosis. In review of this patient’s records, it was noted that the couple had been through multiple rounds of IVF with numerous embryos deemed unsuitable for transfer, either because of the PGT-M noting the 5T allele and the paternal CFTR variant, or because of aneuploidy. The ECS led this couple down a path that cost them many thousands of dollars and years of fertility treatments, with countless discarding of embryos that likely would have never manifested any health concerns, let alone left-threatening ones, as a result of this genetic variant.

Despite evidence suggesting that there is not a benefit to using PGT-A for most patients, it is sold to vulnerable patients with claims that the test will increase the likelihood that they will not only have a baby, but also a “healthier baby”. Similarly, ECS is presented to patients as a test that will screen for “serious” diseases and help lead to better health outcomes. In fact, in many cases ECS may lead to testing of embryos for variants of debatable clinical significance, and potentially to discarding of embryos that could have resulted in babies that do not actually have the condition that is being tested for.

The marketing claim for both of these tests is a promise of healthy babies. A claim that indeed sells tests, but is far too simple and often not true. Even if the evidence was there to prove that these screens statistically “improved outcomes,” they are selling false reassurance as no screen can remove the chance of most, let alone all, possible future health concerns that have a genetic component.

I believe that the messaging for preimplantation genetic testing with polygenic screening (PGT-P) will be much the same as what we have seen with PGT-A and ECS. Similarly, PGT-P will lead to another list of probabilities and uncertainties for patients to grapple with when considering next steps for building their families. Possibly information that may feel helpful to some, but also will be toxic information to others. Risks and probabilities for adult onset conditions for which they cannot unlearn once they are told, and so will likely carry through with them from the time they (hopefully) conceive through their children’s whole lives. Assuming evidence can be proven, information that will likely become outdated shortly after conception and yet will likely never reach the families as their children grow.

While there are some people who may be interested in undergoing IVF for the sole purpose of PGT-P, I don’t believe that there is a big market of people who are clamoring for testing for the sole purpose of selecting amongst a list of probabilities for adult-onset, multifactorial conditions. The cost of IVF is high – not just the financial cost but the physical and emotional toll as well. It is difficult to imagine many people, even those for whom money is not a concern, subjecting themselves to the difficult treatments required for IVF without significant concerns.

To imagine where things may be headed in the area of polygenic embryo screening, we can follow the money, or the promise of money. In that way, I can imagine that PGT-P will soon go the way of PGT-A – where it is promoted and marketed as a test that can improve pregnancy outcomes, regardless of whether the evidence bears that out. The market for PGT-P for all patients undergoing IVF would be much more lucrative for the testing companies and the clinics that offer it. And while there are often good intentions and ideas behind evolving technologies, it is often the commercial incentives that drive these tests forward.

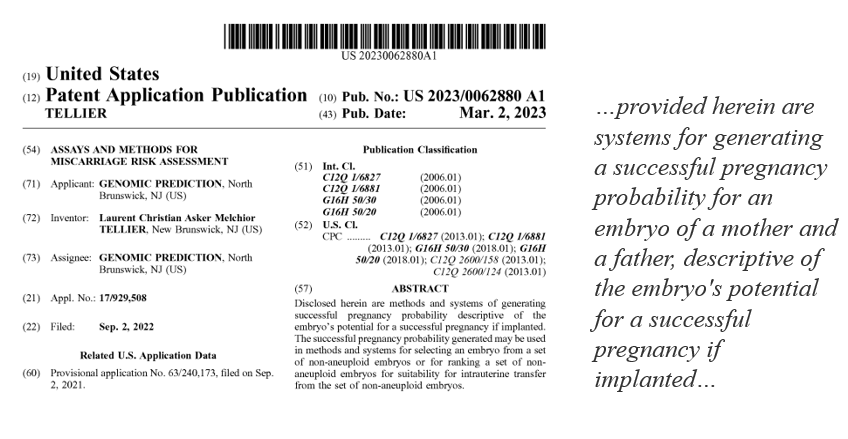

There is already some suggestion that this is the direction that PGT-P companies are headed. The LifeView PGT-A/PGT-P test is being advertised as improving live birth rates on their partner private equity owned fertility group Ovation Fertility’s website. Genomic Prediction also holds a patent for Assays and Methods for Miscarriage Risk Assessment, which appears to include a patent for polygenic risk scores for predicting whether or not an embryo will result in miscarriage versus a successful pregnancy.

If this is successfully marketed and if there continues to be no regulation to require proof of benefit and lack of harm, I think we can expect this testing to be increasingly common. Patients will be hooked by the promise that this testing may help them achieve their hopes of bringing home a baby. And once hooked, they will need to wrestle with the information that these tests claim to provide, predicting the health risks for their imagined children, and not being unable to unknow it once reported and embryos selected or discarded.

Also noted throughout the conference, is that genetic counselors who work for the PGT and ECS companies are often the ones who are consenting patients for these tests and also those who review the results. It seems misguided to think that employees of companies who sell test products are the ones best suited to obtain informed consent; consent that truly is based on a patient’s understanding of the overall benefits, risks, and limitations of these, tests as well as the alternatives (often an alternative being not to do the tests). This is another reason why our work at Genetic Support Foundation is so important. We advocate for genetic counseling that is separate from selling tests. We believe that all patients considering reproductive genetic testing of any kind should have access to independent professionals who are not biased by the profit motives of their employers, even if that bias is subconscious. Avoiding conflict of interest is important in all areas of medicine and genetics, but it is especially crucial in reproductive health.