By Devin Shuman, CGC (she/her)

We need to talk about genetic exceptionalism. By this I mean, the notion that genetic testing is so groundbreaking that it has replaced the entire diagnostic process for many conditions. Which leaves us with the question of, what do we do when we hit the edge of genetic knowledge and technology? Because there will always be a limit to what we currently know. Genetic testing is not the end all of medicine or diagnostics, though it can be a powerful tool.

Genetic testing and the diagnostic odyssey

As a genetic counselor with a genetic condition, my story is exceptional in that it is the exception to the rule. From my family’s upper-middle-class, educated, white privilege with personal connections to doctors and researchers, to my own privilege as straight-cis passing, obviously abnormal findings on blood work, and a literal degree in genetics – my path to an answer is not accessible to 99.99% of the undiagnosed world.

It typically takes over 5 years for individuals diagnosed with rare diseases to receive the correct diagnosis, often after a journey seeing dozens of specialists known as the “diagnostic odyssey.” But what happens after you put half a decade and thousands of dollars into your “odyssey” and are left with no answers and (often) medical trauma? In the US alone, it is estimated that 25-30 million people have an undiagnosed condition, meaning that nearly 1-in-13 have chronic symptoms from an underlying condition that we cannot identify.

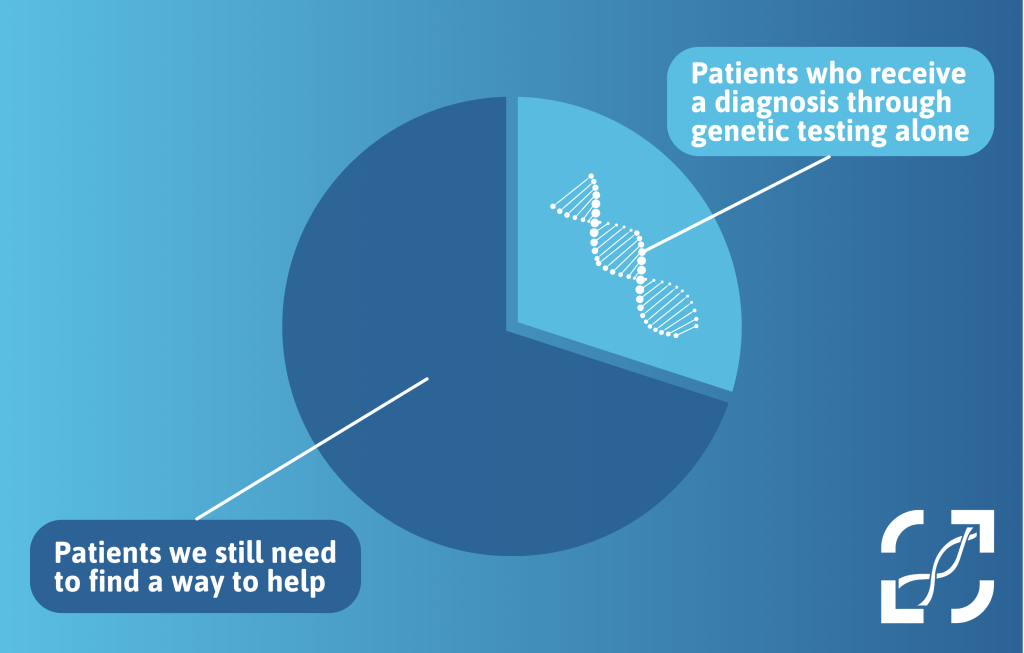

It is estimated that 80% of rare diseases are genetic in origin, so it is not surprising that many medical professionals have turned to genetic testing to diagnose patients. But we need to all remember that genetic testing can only identify the cause of conditions, such as epilepsy, neuromuscular, mitochondrial, and intellectual disabilities, approximately 20-40% of the time. This means that genetic testing is leaving, on average and at best, 60% of patients without an answer while we wait for knowledge and technology to catch up. Healthcare needs to be designed to help everyone, not just those with easier to find answers or treatment options.

The genetics bottleneck

Is dysmorphology and diagnosing based on clinical symptoms an imperfect art form? Naturally. As genetic testing becomes more accessible, are we finding out that we were wrong in the diagnosis we gave many patients? Yes. But to view one modality as the gold standard, a modality that we will always think is “the best it’s ever been” but will also naturally be “the worst it’s ever been,” is a dangerous approach to medicine and patient care. Especially in a world ruled by diagnostic codes, the more we hold up a science that is leaving on average half of patients behind, the more we leave “do no harm” behind as well.

Practicing as an often standalone GC (working with other GCs but not paired off with another medical professional like a physician), I am acutely aware of the limitations of my scope of practice. I cannot order the additional studies such as non-genetic labs, imaging, or biopsies to further investigate an individual’s symptoms, nor provide the physical exam needed to confirm a clinical diagnosis. I am very frank with my patients about the limitations of what I can help with and the hard-to-cope with reality of when I have little left to offer. I often end with referrals to in-person geneticist clinics and/or programs like the Undiagnosed Disease Network (assuming their funding even survives).

However, in a country with a long-term, alarming lack of genetic professionals, waitlists for genetic clinics are now years long – forcing these clinics to prioritize which referrals they will see. This means that often the conditions most likely to have an identifiable genetic cause are being prioritized, with some clinics making the tough decision to decline referrals for conditions that can currently “only” be diagnosed through clinical criteria (i.e., for which there is no genetic testing currently available, such as hEDS).

One of the hallmark skills of a geneticist is performing an in-depth clinical assessment for subtle features of genetic disorders, but many genetics clinics are now requiring patients to have already had testing (imaging, biochemical blood work, etc.) to “prove” that they have classic features of a condition before they will even accept their referral. Where does this leave patients when other providers are not trained or comfortable with performing this workup? Additionally, due to this backlog of patients, if genetic testing is inconclusive many accepted patients are later told “no follow-up is necessary,” leaving them often feeling lost knowing what their next steps are or how to check-back in as updated testing becomes available in the future.

Those who are left behind

For what often feels like the vast majority of individuals with complex, varied health needs, these changes leave many without a medical home. What’s worse, other providers often view negative genetic testing or a referral being declined as proof that the diagnosis in question has been ruled out and (sadly) that the individual’s symptoms may not be “real” or are psychogenic in nature. As a field, we have to reckon with the fact that we are failing undiagnosed patients by not pushing back harder against the notion that genetic testing is the gold standard for diagnostics. We also have to reckon with the fact that barriers to receiving a diagnosis will be exacerbated by fewer geneticists trained every year, and that the next generation of general medical providers may not be trained in the lost art of genetic clinical evaluations.

The genetic clinic bottleneck is not the only barrier to accessing genetics care. Assuming a patient even has insurance and an affordable deductible – insurance policies may only approve testing once in a lifetime or only approve testing if you’re under the age of 18. Personally as a GC I”ll never forget my first case of providers refuse to order a basic enzyme test that is the gold standard method of diagnosing a condition because “we need to wait for genetics,” leading to delays in lifesaving treatments for a dying newborn. More commonly, recommended screenings get missed due to “the genetic testing was normal” (such as cardiology declining to follow a patient with a strong family history of aortic dissections). Even for more generic population-level screening such as prenatal screening, no matter how many times you discuss “residual risk,” many individuals (including providers) walk away with the impression that “this condition has been ruled out” or, even more concerning, that the genetic testing somehow provides a health guarantee.

Did we prove through advances in genetics that many previously given clinical diagnoses were wrong? Yes. But is that not part of the learning process? Where do we draw the line between “trying our best and being wrong sometimes” and “being scared to be wrong to the point of leaving millions of patients without an advocate or home in the medical world?” All I can offer these patients is honesty that I am sorry that they have hit the limit of our current genetic knowledge, that what they are experiencing is impossibly hard and frustrating, and an explanation of why we cannot find answers at this time.

I am beyond proud to work at an organization where our tagline centers the human experience, not the technology: “Genetic healthcare doesn’t start with a test. It starts with you.” But so many individuals now only gain access to a genetics health provider after testing has been done, and never gain access if that testing is uninformative. I know that we’re an overstretched field inside of a broken healthcare system but we can and need to do better. Genetics is a powerful tool, but it is not so exceptional that it should be the only tool in your toolbox.